Guy Ritchie's The Covenant might be the Call of Duty movie you've been looking for

Orrrrr, you could just play the game

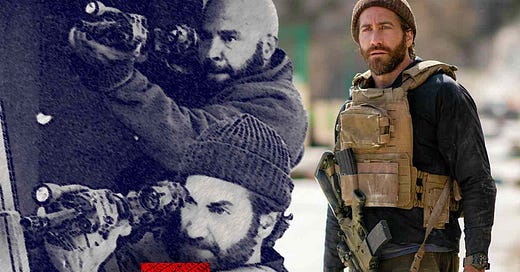

Director Guy Ritchie tackles the war film genre for the first time with The Covenenat (sorry, GUY RITCHIE’S The Covenant, if you please), which is an attempt to capture the “bond” of a combat soldier with his interpreter and the price of that bond when it comes to repaying a debt. The debt in question involves Master Sergeant John Kinley, played by Jake Gyllenhaal, being saved by his interpreter, Ahmed, played by Dar Salim. It’s no ordinary save, however, as Ahmed carries Kinley across miles of hellish Afghanistan territory after they are ambushed by Taliban fighters and summarily hunted.

Pulling the wounded Kinley to safety in a wooden cart across the mountainous terrain back to Bagram Air Base, taking breaks to sleep, eat, and smoke heroin, Ahmed brings Kinley back safely, but is immediately put back on the run from the Taliban, who put a price on his head for helping the Americans (and, possibly for killing a bunch of disposable Taliban along the way).

But, Kinley can’t live with that debt, knowing that Ahmed is on the run with his wife and newborn baby, put in that position for saving his life. So, through a bunch of backwards channels, Kinley takes it upon himself to go and get Ahmed to bring him back to the States, which all comes together pretty quickly and with barely an inconvenience, the details of his secret mission skimmed over as if the writers (Ritchie, Ivan Atkinson, and Marn Davies) put a pin in that part, but forgot to return to it when they started filming.

Such is frequently the case with The Covenant, a fictional war film thriller that attempts to shine a light on a real-world issue (interpreters being promised a visa to the US, with many of those promises left languishing), while also trying to be a deep, introspective drama about loyalty and debt. It doesn’t stick the landing on either but does manage at least a few good moments that ultimately make it more entertaining than it deserves to be.

Gyllenhaal is solid in the leading man role, if not a bit too rigid and straight-laced for the performance to be anything special. He gets the job done and is a fine presence throughout and you want to see him succeed, but he’s either pulled back or pushed forward at the wrong times throughout the film. There’s a scene where he stops to take a break with Ahmed while they’re on the run from the Taliban and it’s the first moment he’s had to think about the fact that he just lost a bunch of men in the process. The struggle to keep it together in that moment is the finest of Gyllenhaal’s work in the film, as well as one of the moments that help the film rise above what would otherwise be little more than a serviceable action yarn.

Dar Salim, on the other hand, gets the heavy lifting (quite literally) midway through the film and shows some real grit and emotion when called upon, making for a memorable performance that will surely get him the recognition he’s earned. Still, his story is so pared down and simplistic, missing out on the meat of who he is, why he’s helping the U.S. as an interpreter, and why he’d risk it all for Kinley. The “why” always matters. It actually matters the most. And if the only “why” given is an expository statement that “the Taliban killed his brother” then we miss out on what makes the character tick. Fortunately, Salim makes up for the lack of development with presence and emotion.

It’s a shame, though, as the interpreters I’ve personally worked with in Iraq and Afghanistan were always interesting, complex, and frequently hilarious people. They were invaluable in doing our jobs there, and we did form bonds with them. Frequently, they helped us understand the strange and violent new world we were operating in better than anyone else could. And they told us straight. They had families, dreams, flaws, and everything in between. I remember working with one interpreter who just wanted to read English to me and have me help him correct pronunciation and I found it to be an honorable thing. I saw their struggles, their risk, and their desire to rise above their station. Without interpreters we were a reckless, wild, blunt instrument and I think The Covenant misses out on humanizing these men and women beyond the stereotypes.

Ritchie has more than proven to be a strong, stylish filmmaker who knows how to bob and weave through a narrative with manic grace, but with The Covenant it feels like he’s restraining himself when he should be unleashing, and vice versa. Many of the action scenes feel predictable and sluggish, like Call of Duty gameplay, complete with a voice-on-the-radio guiding you through it at times. In many ways, The Covenant is a live-action Call of Duty movie, right down to the variety of missions that have you using different weapons and techniques in different scenarios, all in the name of making it fun and exciting, but it’s far more fun when you’re in control, rather than just watching “cinematics” in real-time, which is pretty much how The Covenant plays out.

In terms of military accuracy, however, The Covenant is all over the place. There’s so much nonsense that most audiences will never get, while those that have served and operated, will wince and frown at the obvious oversights. It gets the job done, but there are so many silly things that get tossed out the window for the sake of entertainment and ignorance, including the rank structure, tactics, weapons, uniforms, regulations, command & control, and…okay, they pretty much just have a shell of how all this works in the real world.

It’s fine if folks enjoy it for what it is, but the first person that says The Covenant is an accurate war film needs to start fucking pushing (that means to do push-ups until I tell you to stop). It’s as accurate as Call of Duty, which is a cherry-picked blossom of highlights that plays along with reality just enough to convince you that it’s real. The rest is just made-up bullshit to keep the plot moving.

For The Covenant, the film falls into a big, fat pit of convenience when Kinley returns home to the States after surviving his ordeal, thanks to Ahmed. He’s troubled, can’t sleep, and feels indebted to Ahmed, who he learns is on the run with his wife and kid. The trouble is compounded when Kinley can’t get a Visa for Ahmed and his family overnighted, as there's a large amount of red tape to get through. After failing to make any progress by calling the government line (Veterans will recognize this as the most accurate part of the entire film), Kinley decides that he’s just gonna have to go on back to the ‘Stan and rescue this boy himself.

Ah, if only it were as simple as it is in the movies. Kinley is fully recovered from his injuries of being shot twice and smashed in the head with a rifle butt after seven weeks, and apparently in the military world of Guy Ritchie’s The Covenant, soldiers only have to show up to work when they are deploying. Otherwise, it seems like an endless block leave where they run a business and hang out at home all day. I guess the argument could be made that he’s a National Guard soldier, which is always possible, but they fail to make any mention of that.

That may be a “big whoop” detail to everyday civilians, but it’s a thorn in the side of those that serve and have served, as we all know god damn well that when leave is over, your ass is back at work, in uniform, and that’s fucking that, no matter which special operation community you work in.

Beyond that, Kinley getting his plan to go back to Afghanistan through civilian contractor channels is blindingly silly and convenient, sidestepping some real stakes when it comes to pulling off such an endeavor. The set-up or “out” for these situations is always some goofy wild card that gets Kinley what he wants and needs, as he treks to Afghanistan alone to find his interpreter. It sounds heroic and badass and it would be if it were actually true, but that’s just not how it works.

Having Kinley face some real consequences for his actions, for breaking military protocol, and even attempting this type of thing on his own feels short-sighted. The truth is that a man like Kinley would no doubt have several operators that would willingly go with him to rescue Ahmed, without question or hesitation, but the movie sidesteps such a thing in favor of a Rambo-eque mission that all just kind of comes together. There’s no real struggle in this scenario, making it that much more of a video game than a movie.

Having the odds stacked against Kinley, making him have to truly struggle and sacrifice to rescue Ahmed would’ve been a far more compelling, interesting, and realistic story, not to mention one with some real suspense and stakes. Sure, he’s overwhelmed by nameless, faceless Taliban fighters, who unironically take the villain role inhabited by Russia throughout 80s in a slew of action films. It makes sense to a degree, but they come off as bad guys pulled from Team America: World Police, rather than actual Taliban.

I acknowledge my bias on all of this, which will forever ruin war films for the rest of my life (although in some cases, it does make them better). I sound like a grumpy war vet (good, cause I AM), and it’s the price of having lived the good, the bad, the ugly, and the bureaucratic of the military. You can’t unspin that bottle and it’s what makes watching The Covenant and accepting it at face value impossible. It just doesn’t do enough work to be convincing.

In the end, Guy Ritchie’s The Covenant at least makes up for his last film, the abysmal Operation Fortune, which is the director at his most lazy. The Covenant is lazy in other ways, but it’s also riddled with promise while being goofily entertaining, even if it’s far more fun to just play a Call of Duty campaign. The odd thing is that The Covenant has the shell of something that could’ve been truly amazing and powerful but instead exists as a simplified actioner that runs out of ammo too soon, likely because everyone is always shooting on full auto, rather than taking careful and precise shots like they were trained to do.