“People are always like, ‘Batman can’t kill.’ So Batman can’t kill is canon. And I’m like, ‘Okay, well, the first thing I want to do when you say that is I want to see what happens. And they go, ‘Well, don’t put him in a situation where he has to kill someone.’ I’m like, ‘Well, that’s just like you’re protecting your God in a weird way, right? You’re making your God irrelevant.'”

That’s a quote from director Zack Snyder, appearing on Joe Rogen’s podcast and discussing his deconstructionist take on the character of Batman, which appeared in both his Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice, and Justice League films for WB. Snyder is no stranger to adapting comic-book properties, having also filmed an adaptation of Frank Miller’s 300, as well as Alan Moore’s Watchmen, before diving into the broader world of DC, which ultimately ended in his exit from the studio (before returning to complete his “Snyder Cut” of Justice League for HBO Max).

Snyder’s words have reverberated through fandom, who have latched onto his words and formulated many different takes, some for and against what the filmmaker shared. It’s not a new argument, and it has continued to rear its head every single time a superhero movie comes out, especially when it’s from a filmmaker that has a more specific vision than, say, a made-by-committee Marvel or DC film. The question constantly arises in these fan spheres of whether or not a superhero character, particularly one of prominence and popularity, should kill their enemies. As mythical beacons of the comic-book page, many of these characters have become larger than life, standing for a model of humanity, rather than a real-life character faced with real-life decisions.

Religion and Mythology: Gods, Monsters, Heroes, and Humans

To understand these larger-than-life characters, we must first understand myth. Per Mirriam-Webster, myth is defined as:

Mythology

noun

my·thol·o·gy mi-ˈthä-lə-jē

plural mythologies

Synonyms of mythology

1 : an allegorical narrative

2 : a body of myths: such as

a: the myths dealing with the gods, demigods, and legendary heroes of a particular people

b : mythos sense 2 Cold War mythology

3 : a branch of knowledge that deals with myth

4 : a popular belief or assumption that has grown up around someone or something : myth sense 2a defective mythologies that ignore masculine depth of feeling - Robert Bly

The earliest mythological characters were shown in cave paintings, before graduating into a multitude of cultures that include Greek, Norse, Mayan, Native American, and countless others throughout centuries. What all of these mythological tales, characters, and situations represented was some form of commentary or lesson about life which served as both entertainment and guidance, frequently as a cautionary tale.

Religion as well could be seen as a form of myth, be it Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, etc. Many have familiar motifs and recurring themes, all of which add up to a belief in a power greater than oneself as well as a set of “rules” in how to live (and how not to live) as a human being. Be it Jesus, Muhammed, Moses, The Trimurti, Buddha, etc., there is always a figurehead that stands as the representative of humanity (as it pertains to a particular culture), giving hope and value to the often chaotic reality of the human experience.

So, now that we’ve defined mythology on a broad level, let’s take a look at how these mythological (and religious) figures behaved in their historical tales, particularly, whether or not they killed their enemies, despite outlawing such things from their human subjects.

Certainly, the Old and New Testament God of The Holy Bible has killed, vanquishing the entire planet with a flood at one point and taking out various groups and individuals throughout that era, men, women, children, and animals alike. The Ten Plagues of Egypt is another example of God’s Wrath in the Old Testament, which again shows that those we worship can exercise their vengeance in horrific ways.

Jesus, the Son of God, was a peaceful messenger and never inflicted violence upon another that was ever documented. His sermons were filled with love and compassion for humanity, and he performed miracles that brought life and hope, before being crucified. His persona in The Book of Revelation, however, paints the picture of a warrior who returns to Earth, riding upon a white horse wearing a robe dipped in blood and armed with a double-edged sword, ready to battle the demonic forces occupying Earth.

Muhammed, The Prophet and leader of Islam, was constantly at battle throughout his adult life, leading multiple military campaigns against his enemies, resulting in at least a thousand deaths, according to scholars.

In Egyptian mythology, The Myth of the Heavenly Cow has a similar body count to the Old Testament God, in which the sun god, Re, feeling opposition and rebellion from his human subjects, sends the goddess Hathor to destroy his detractors. Hathor enjoyed immense success in killing off the human rebellion, later taking the form of the vengeful lion-headed goddess Sekhmet, who “waded in the blood” of the Egyptian populace she massacred.

When it comes to Greek Gods, the tales are far more fantastical and cinematic, making for a vibrant world of cautionary tales amidst distinct heroes, villains, and monsters. From Zeus to Artemis to Hera and beyond, death was a constant cycle of their existence, which frequently involved some form of long-term torture before the eventual journey to the underworld. The Greek Gods were nothing if not spiteful in their delivery of punishment, which frequently made them appear more frightening than heroic.

Over time, modern-day religious figures took the form of the Greek and Egyptian Gods, as the shifting tide of culture over centuries brought new myths to shore. Only in the last century have pop-culture icons and fictional characters who originally appeared in novels, comic books, movies, and TV shows, become the new gods, so to speak, acting as mythological manifestations of the human experience in the current era.

Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Captain America, Spider-Man, Daredevil, The Punisher, Luke Skywalker, Yoda, Wolverine, Aragorn, Aquaman, The Crow, Guts, Demon Slayer, Samurai Jack, and the list goes on and on. It’s near infinite, at this point, when it comes to fantasy characters set within their own universe, who have created an entire set of rules, idioms, characteristics, icons, and circumstances, all of which exist to reflect the human experience in some way, shape, or form.

Yes, they all share one more thing in common, which is slightly different than any other myth before them: they are primarily made for entertainment and commerce. The creator may well have created their characters and universes out of the desire to make art, but the means to see that art is through commerce, as nearly all of these creations are delivered utilizing a pay-to-see/read/watch format. For the first time, our Gods take credit card payments.

The Golden Era of Censorship

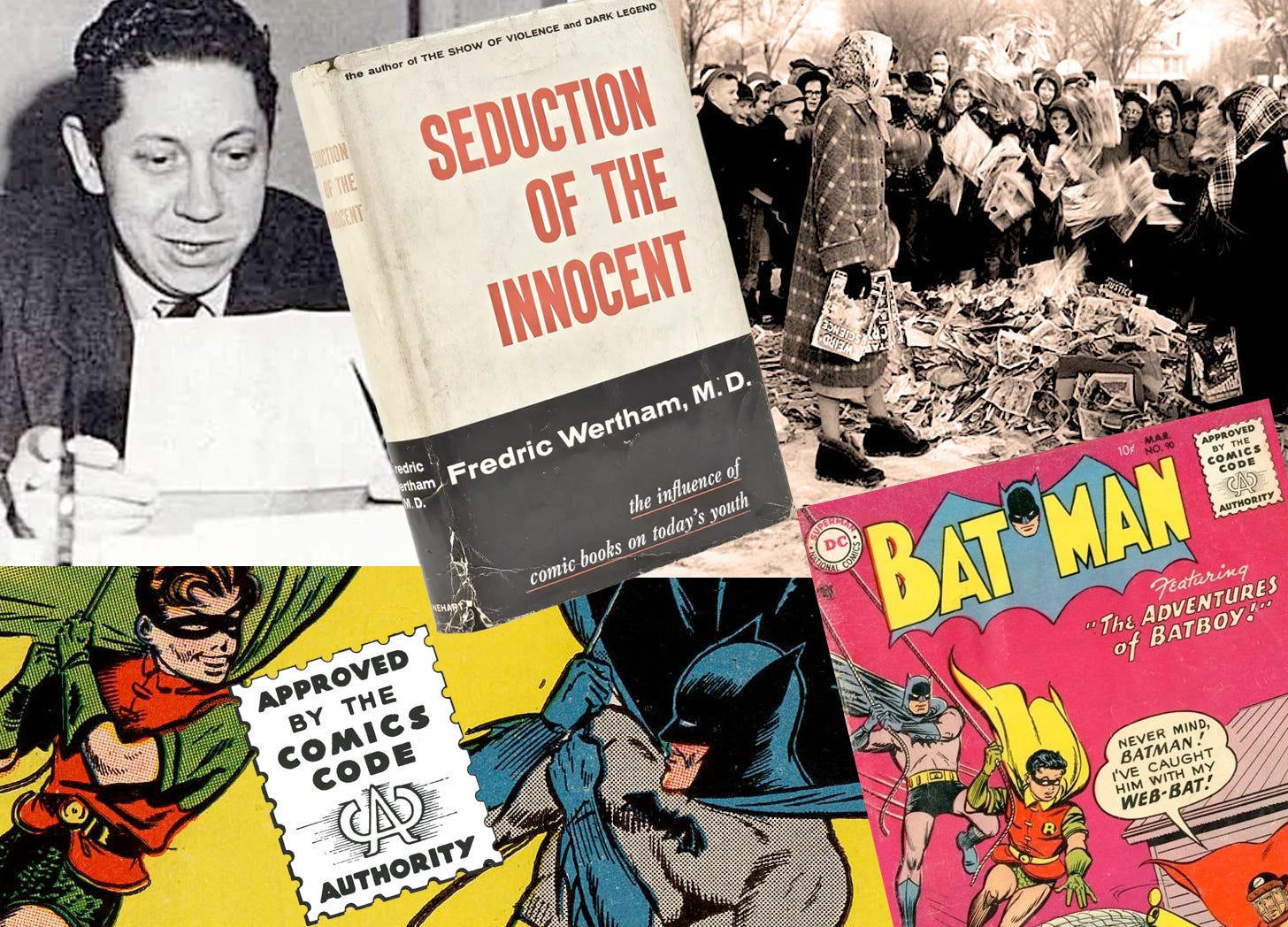

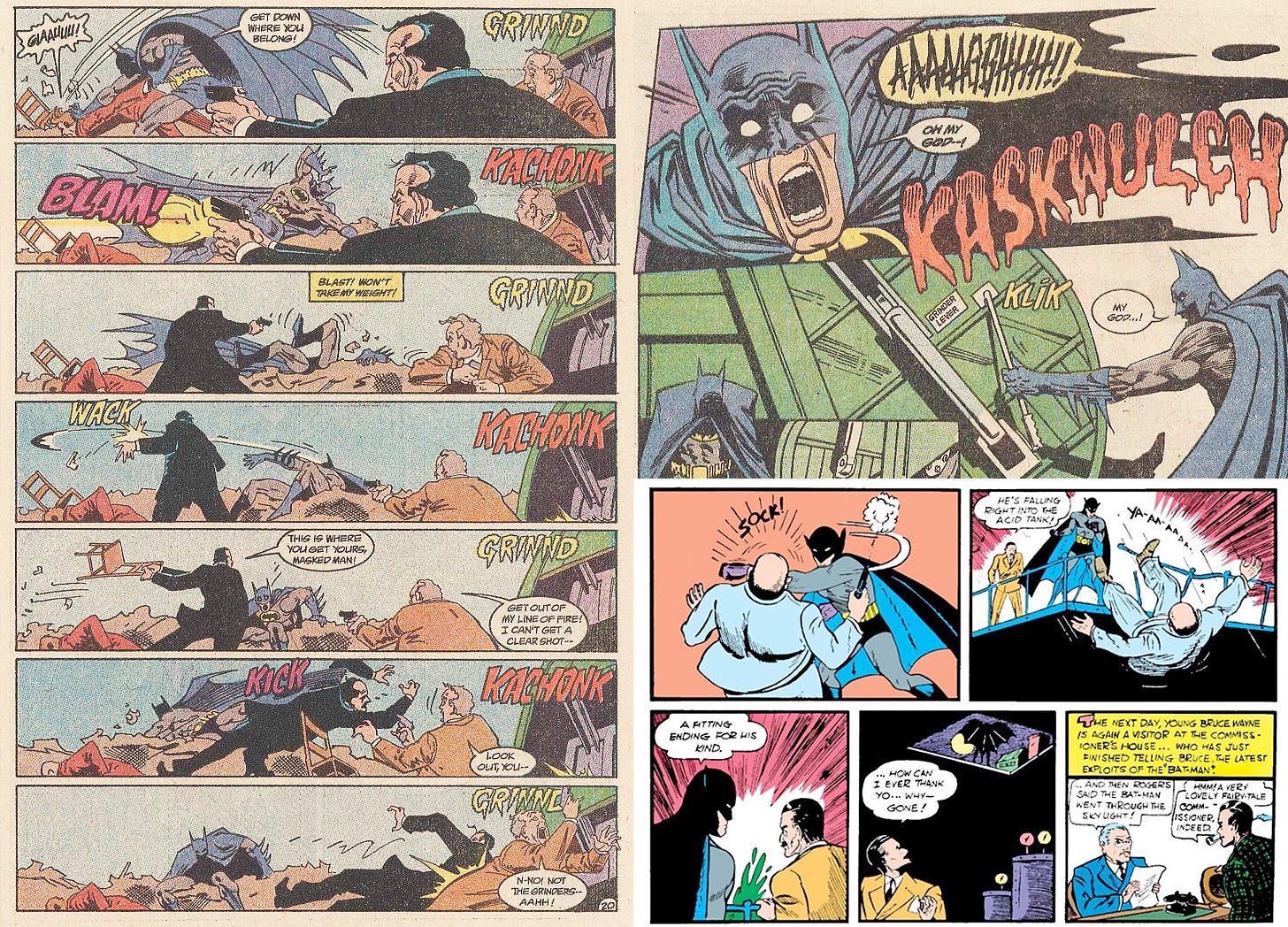

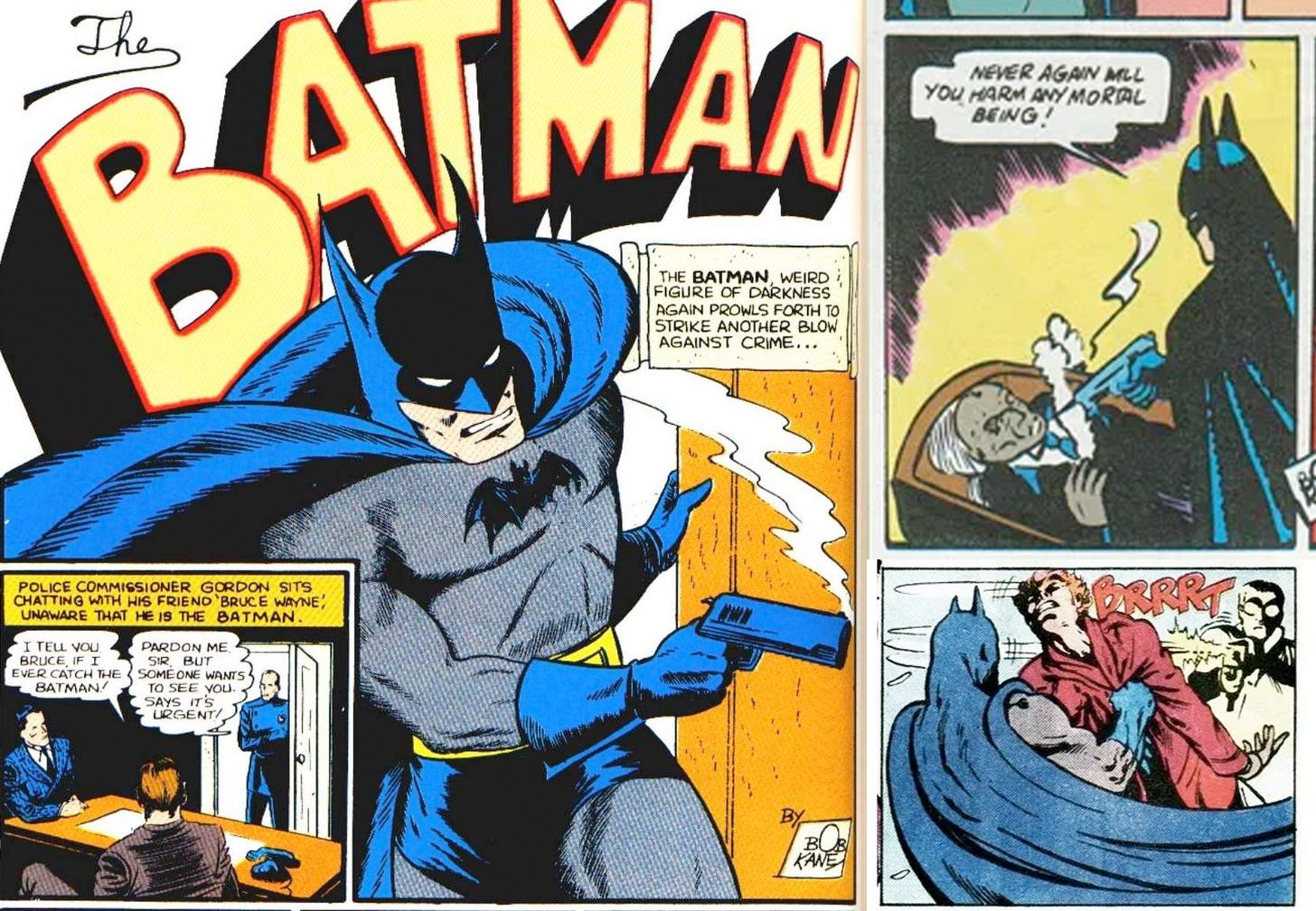

During the Golden Era of DC Comics, the character of Batman (created by Bill Finger and Bob Kane) was more of a pulp hero akin to The Shadow, even wielding a gun and killing off his enemies by the end of the issue. However, then-editor Whitney Ellsworth stepped in when parents began to complain that their children were reading violent comic books, and instituted the now famous “no-kill” rule for ALL of the DC heroes, saying, "Heroes should never kill a villain, no matter the depths of his villainy."

This led to The Joker being spared after their first encounter, creating a legacy villain that has lasted for decades. As Batman grew more and more popular, his means of justice became much more sanitized and “kid-friendly” which was done, it seems, largely for the benefit of profit, rather than some moral code of righteousness. This is where the aspect of commerce plays a key role in the development of the “no-kill” rule. It wasn’t something built into the character of Batman upon inception, but rather a reaction to his popularity (i.e. sales), not to mention the postwar traditionalist values that were being pushed into the 1950s.

This led to the publication of Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent, in which he argued that comic books led to juvenile delinquency. Parents began to campaign for the censorship of comic books, which led to the creation of the Comics Code Authority, which had a full list of guidelines for comic publishers to follow in creating their stories. This kind of censorship is not unheard of even today, as numerous parental groups attempt to ban a multitude of books, usually as a result of their political beliefs, left or right. There was even a time when parents gathered to protest rap music and attempted to have it outlawed. Surely, we haven’t seen the end of such censorship grabs, which seem to come in waves and in response to whatever form of entertainment is most popular.

Below are the full guidelines for the Comics Code Authority:

Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gunplay, physical agony, the gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated.

Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation.

Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.

No comic magazine shall use the words "horror" or "terror" in its title.

All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly, nor so as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.

In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.

Profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity, or words or symbols which have acquired undesirable meanings are forbidden.

Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.

Suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture is unacceptable.

Nudity with meretricious purpose and salacious postures shall not be permitted in the advertising of any product; clothed figures shall never be presented in such a way as to be offensive or contrary to good taste or morals.

Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.

Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed. Rape scenes, as well as sexual abnormalities, are unacceptable.

Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

Seduction and rape shall never be shown or suggested.

Reading this list today, particularly as a creator and artist, is maddening. It’s not only a direct violation of the First Amendment in every single way, but it is, by all accounts, the antithesis of art.

The Comics Code Authority was enforced up until 2011 when DC finally stopped utilizing it altogether, following in the footsteps of Marvel in 2010 and everyone else. Today, there is no Comics Code Authority, but many publishers have instituted a maturity rating for their books, which runs the gamut in terminology from publisher to publisher.

Now, even though the Comics Code Authority was most heavily enforced in the 1950s, the generations that followed began to loosen the reins a bit and start to experiment with darker, grittier, and more realistic themes, with some books taking on a mature rating label. In the time since the Comics Code Authority was instituted, Batman would still find his way into killing off a villain here and there, including KGBeast, but he mostly adhered to this “code” which many writers began to adopt as something built into the character, rather than the censorship flex it was born of.

The Bat-Bible

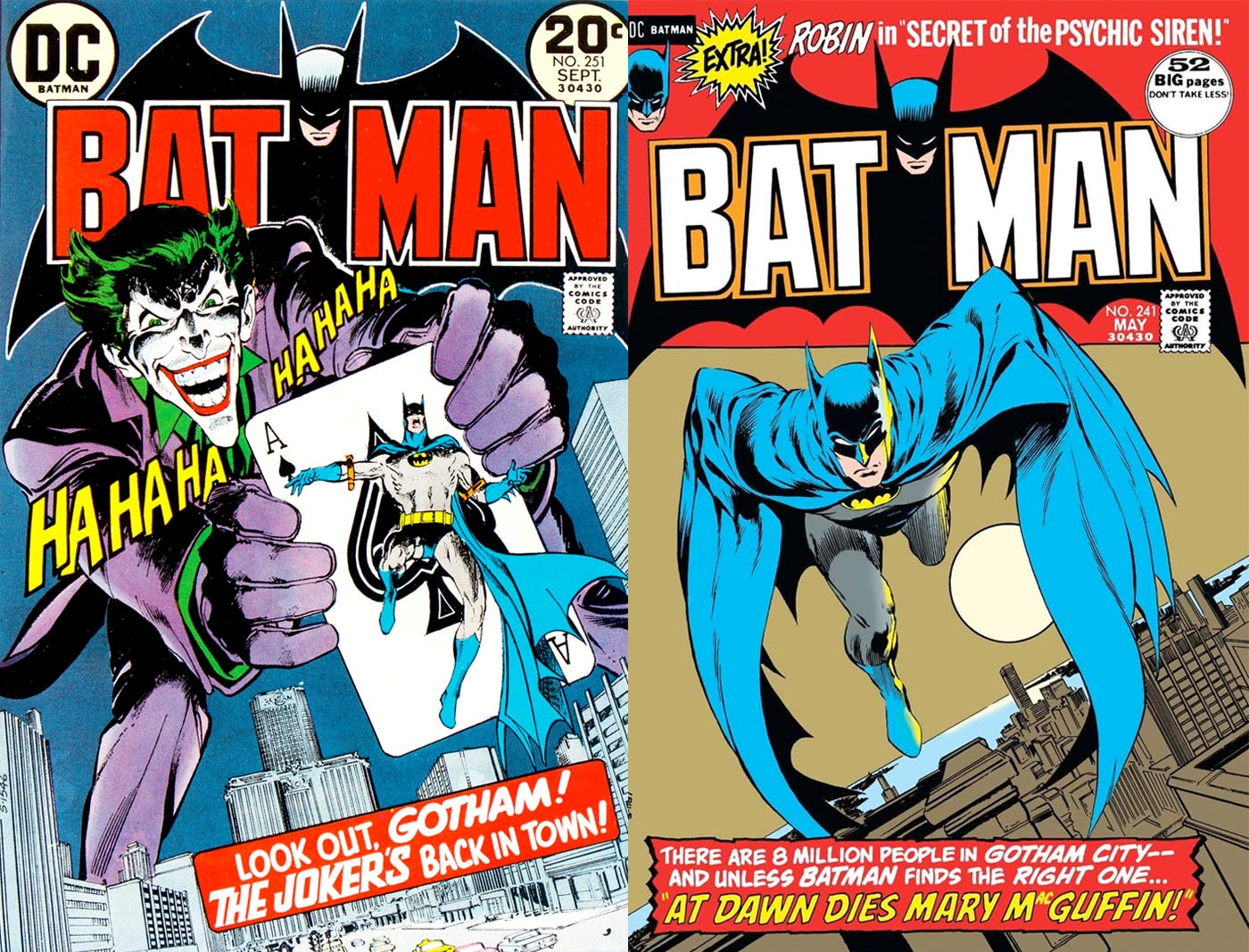

One of those writers was Batman writer and editor Denny O’Neil, who served as a writer and editor on various Batman titles throughout the 70s and 80s. O’Neil, along with artist Neal Adams are frequently noted for taking the campier version that Batman had become during his heavily censored era and reinventing and reinvigorating the character in a way that honored the roots that both Finger and Kane had done initially, save for the propensity to kill.

Sometime in the late 80s, O’Neil created what is known as the “Bat-Bible” a living document that’s been handed down over the years as both a manifest and guideline for those creators that took on the mantle of the bat on any of the numerous titles he starred in. While not necessarily something that had to be adhered to, the concept, the principles, and the general breakdown is something that must have resonated during O’Neil’s era, as most of them are prevelant today, save for some deviations here and there.

O’Neil was very particular about Batman’s No-Kill Rule in the Bat-Bible, which I’ve included below (you can read it in its entirety HERE).

First, let us agree that Wayne/Batman is not insane. There is a difference between obsession and insanity. Obsessed the man surely is, but he is in the fullest possession of his mental and moral faculties. Everything with the exception of his friends' welfare is bent to the task he knows he can never accomplish, the elimination of crime. It is this task which imposes meaning on an existence he would otherwise find intolerable.

He is tough, but not brutal. He uses violence willingly and often, but never to excess, and never with pleasure. He does not enjoy it. And he never kills. Let's repeat that for the folks in the balcony: Batman never kills. The trauma which created his obsession also generated in him a reverence for that most basic of values, the sacredness of human life. If he was not consumed with the elimination of crime, he would not be the Batman. And if he did not consider human life inviolable, he would not be the Batman, either.

I think O’Neil had a deep understanding of Batman and his mythological properties. Much of how he outlines the character is very god-like, with everything about the character being beyond the normal scope of a human being, while still being only human (genuis IQ, physical specimen, endless money, skilled in everything, etc.). It’s a common trope amongst many human superheroes and it fits the mold. How else could they do what they do, particularly if they don’t have superhuman or mutant abilities?

If Batman knows that he will be Batman until he retires or dies (as he already knows that crime will never end), and he will be putting himself in harm’s way continuously, forcing a violent altercation a large percentage of the time, fighting against everyone from street thugs to criminal masterminds, many of whom have guns, knives, bombs, toxins, etc. at their disposal and with the full intent to use them, Batman must contend with mass murderers and the possibility that he could be put in a position of having to kill them if all else fails.

If it means the death of innocents, the very people he’s trying to protect, would Batman willingly turn the cheek and let them die so as not to break a rule that would save them otherwise? The easy answer to that is to fall back on the “he’s just a comic-book character” argument, which is the cowardly way out of it. Yes, of course, a writer can write any kind of story they want that would never ever put Batman in such a situation. In a fantasy world, it’s the puppeteers that control the narrative, not the guiding unpredictable force of reality.

In the real world, Batman would face such predicaments regularly and he would have to have an answer long before he faced them.

While I agree with O’Neil’s Bat Bible in many areas, I think the reasoning behind his Batman No-Kill Rule is contradictory. Batman upholds the rule because he believes every life is sacred due to his own trauma, but would that belief not be tarnished if innocents died under his watch, especially when he had the ability to help them instead of letting a villain get away with murder? To me, that would render Batman futile. If he cannot act decisively, with all that IQ, all those gadgets, as a great detective, a physical specimen, then what good is he really doing?

Now, does that mean Batman should just kill off villains immediately and be done with it? No. That’s The Punisher’s job, and his trauma is born of a multitude of different factors that make his form of justice unique to him. But, by the, say, sixth time Joker has broken out of Arkham and killed hundreds more people (let alone Batman’s own Boy Wonder), wouldn’t it make sense from a societal standpoint that Joker be put down? How is he different than, say, Osama Bin Laden or Timothy McVeigh or any other terrorist that is hellbent on the destruction of innocent lives? And if we can’t seem to keep them locked up, then what other choice is there?

Like Aflred says in The Dark Knight, some people just want to watch the world burn. Does that mean we should just stand idly by and let them burn it?

While Batman certainly doesn’t need to fly off the handle and lead with execution-style tactics (a notion already explored in the multiverse via The Batman Who Laughs: The Grim Knight), as I believe that’s not within his character, I believe that his code should reflect the very vigilante trade in which he employs himself. Sometimes, no matter how much he may not want to, he must do what needs to be done, even if that means killing, so long as he’s exhausted all of his other options or has done so in order to protect innocent life.

Accidental Death

Here’s an area that we simply can’t escape in this argument. Accidental death would would be a regular occurrence in Batman’s life if we are attempting to dissect this argument. You would probably be shocked at how many people are killed or disabled with blunt force trauma, particularly being punched by someone as heavily skilled as Batman.

Beyond the fighting aspect, Batman takes part in high-speed chases that create mass vehicular carnage (how many innocent folks do you think were killed off camera in that epic chase scene in The Batman?), be it in cars, planes, boats, motorcycles, and the like. While he certainly would attempt to operate later at night when most folks are in bed, there’s simply no way around the fact that Batman, by trade and proxy, would have the blood of countless innocents on his hands in any kind of real-world setting.

This is always the part where those arguing for the no-kill rule throw up their hands and say “this isn’t reality!” But, if it’s not reality and it doesn’t count, then why should it count if Batman kills on purpose? It’s a situation where one side puts blinders on to the bigger picture. Batman invites death just by being Batman, on purpose or not. It’s something to consider when executing this argument of whether he kills or not. Batman, it would seem, kills whether he wants to or not.

Batman Evolves: From Comics to Movies and Beyond

As comics began to mature, particularly in the 1970s and 1980s, with the children who grew up reading those early books now becoming adults, the stories had to evolve as well, and evolve they did. Certainly, children’s comics were still made and the CCA was followed to a degree, but the cultural revolutions of the 60s, 70s, and 80s paved the way for more violent, more aggressive, and more expressive comics, including Batman.

Batman’s rogues gallery continued to blossom under the no-kill rule: Joker, Bane, Catwoman, Penguin, Riddler, Mr. Freeze, Poison Ivy, Harley Quinn, Killer Croc, Clayface, etc., etc., etc. The list goes on and on, with new rogues popping up every year. If Batman killed them all, then how could they come back later? The easier means to allow a return is to have Batman enforce his rule and end an enemy’s run with a mysterious exit that could mean they were either dead or alive, or, most likely, back in the escapathon that is Arkham Asylum.

The filmed versions of Batman were another story altogether, though. Director Tim Burton had no qualms about violating the “no-kill” rule in 1989’s Batman, nor did his Batman ever state that he operated under such terms. Jack Nicholson’s Joker was ultimately killed by Batman, as was Penguin in the sequel, Batman Returns. Batman may not have shot them in the heart with a pistol, but he was absolutely responsible for their demise, not to mention the numerous hitmen he killed throughout the films via blunt-force trauma, explosions, guns, etc.

The cinematic world of Batman had other plans altogether. However, director Christopher Nolan infused a bit of the “no-kill” rule in his Dark Knight trilogy, but it was more of a “no-guns” rule than “no-kill.” His Batman still let Ras Al Ghul die at the end of Batman Begins, saying to Ra’s: “I won’t kill you, but I don’t have to save you,” before letting him die in a massive train crash. While it may seem like Batman didn’t directly kill Ra’s, he ultimately did. Folks will try to wiggle out of that, but if Batman finds all life precious, then that would never have happened. The same could be said of Two-Face at the end of The Dark Knight. Some will argue that it was the fall that killed Harvey Dent, not Batman jumping into him and knocking him to his death. However, I assure you, it was Batman that killed him, because Batman knocked him to his death.

And, to be clear, I love those aspects of Nolan’s trilogy. I think it shows the way Batman should operate. He goes out of his way not to kill the majority of those he violently grapples with, but in some instances, the only way forward is through and that through is death. If it means stopping a man hellbent on decimating millions of lives or a man about to shoot a child, then whatever means necessary, including death, should be employed, especially if Batman is the only one that can make it happen. It’s not only the right thing to do, but it’s his responsibility to act. Nolan got that, I think. Whether explicity or not, his treatment of the character’s no-kill rule was far more relaxed and realistic.

Enter Zack Snyder, who dismantled the “no-kill” rule, making Batman more no-holds barred in Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice. It wasn’t a Punisher-style rampage by any means, but more of a methodical approach to dispensing with violent bad guys and it made perfect sense within that universe. Hell, it makes sense in any universe. Serving as a pseudo-adaptation of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, Batman’s initial mission was to kill Superman, immediately violating his comic-book code of ethics. But, beyond that, we see Batman branding his enemies, stabbing them, shooting and blowing them up, and even firing a gun into a tank that kills one villain. We saw similar things in Burton’s Batman films, but no one really complained. Of course, we didn’t have the Internet back then either.

Snyder’s Batman takes on villains in a far more direct and escalating way. He starts with the usual bag of tricks, knocking them over, tying them up with grappling gun wires, hitting them with batarangs, or just plain beating the piss out of them. But, when they start shooting him in the head, stabbing him, throwing grenades, Batman does what needs to be done. He escalates, much like a soldier or police officer. It’s called escalation-of-force, and it’s taught in both fields. You always lead with the most non-violent measures, but escalate as needed given a particular situation. This, more than anything, makes sense for someone like Batman and I felt Snyder’s (and Nolan’s, for that matter) characterizations of Batman captured this well.

Batman V Superman was the first time that I can recall hearing and reading about fans being upset over Batman killing bad guys. Up until that point, as someone who had been reading Batman comics steadily since 1989, I had no issue and heard no issues. But, for others, it appeared to be a sore spot. Why were people upset by this, I wondered? It’s not like Batman was gunning people down, but at the same time, in a theatrical model, it made sense that villains would be killed. Seeing events in motion and on a screen made for a very different delivery of solutions than a comic panel, which can easily subside, write off, or otherwise subvert the real-world ramifications of inflicting violence upon another person.

If you scour the Internet, from Reddit forums, content-farm fansites, and of course, X, you will find all manner of arguments for and against Batman’s no-kill rule. Some of them are pretty stupid, some of them are incoherent, some of them are sensible, and some of them are dismissive.

Knowing what we know about myths, religious or otherwise, the ability, desire, and/or willingness to kill is ever-present with gods or god-like characters. Not only do these myths kill, but they do so in great numbers, with vengeful intention, and with god-like judgment. Does that mean that every myth must follow suit? Not necessarily, but if we’re talking about a fictional/fantasy/religious figure that cannot be proven by science to exist, then I’d say that they are capable of anything and everything.

But, what about their code? What about the rules these gods and myths impose upon themselves and humanity? Well, the short answer is that they just don’t follow those rules. They may have rules for others, but when it comes to themselves, they break them as needed or desired. It’s the old, Do as I say, not as I do, so to speak.

The difference with modern myths, particularly with comic-book characters, is that they are created by an individual(s) to have very specific characteristics, mannerisms, etc. to introduce them to the world, but they then pass the character around to other creators who infuse their own ideas into the character, while adhering to a set of basic guidelines as a means of staying consistent, particularly for characters that are appearing in a monthly book with narratives lasting for decades.

Now, imagine a character like Batman who began as a killer with a gun, who becomes very popular, driving up sales and interest among fans, who is then in turn disrupted by the cultural backlash of the era (traditional values) that push for censorship. Now, in order to exist, the character must adhere not only to an internally-mandated no-kill rule, but also a long list of “rules” (IE Comics Code) that restrict the character from evolving past a base-level superhero with arbitrary characteristics. He simply cannot evolve, as he cannot be challenged in any meaningful way that would test his character.

The why always matters, and the why of Batman’s no-kill rule boils down to censorship and sales, which were a byproduct of the era, not something ingrained in the character from inception. It wasn’t something that Finger and Kane wanted. They were of the opposite mind, in fact. To keep making the book, attract new readers, calm the minds of censorship-hungry parents (not to mention authors, Congress, and the like), and keep sales rolling, Batman (along with every other character in DC’s library) was no longer allowed to kill in any way, shape, or form. As a result, over time, writers adopted this as a trait and made it part of his identity, eventually even making it a guiding factor in a “Bible” for future creators to follow.

So, now the question becomes, is how Batman adopted his “no-kill” rule valid when it was born of censorship and commerce, rather than some moral standard inherent in his creation? By that same token, if the CCA is no more and the use of maturity-level regulation is self-imposed, is there still an obligation to carry on the tradition of this rule?

Some would say yes, as it has become synonymous with the character, while others say no, as it was never a true characteristic to begin with. Others might say, who gives a shit, it’s a fictional character who dresses up as a bat and beats people up. None of them are right. None of them are wrong. This, ultimately, is the philosophical argument of the character. In the philosophical argument, you can weigh things as they exist in the fantasy world. You can say that Batman should or should not kill given the parameters of the world in which he exists, which is fictional. Compared to reality, it’s another story altogether.

Fiction vs. Reality

When weighing Batman’s code against reality, it simply doesn’t measure up. This tends to be the conflict when it comes to Batman on film, as it’s near impossible to portray Batman not killing someone, even inadvertently. In the latest big-screen endeavor, Matt Reeves’ The Batman, Robert Pattinson’s Dark Knight pushes the “no guns” rule with Jeffrey Wright’s James Gordon, who replies “Hey man, that’s your thing.” This is just after Batman led a high-speed pursuit on a rainy highway at night that no doubt left countless innocent civilians dead. It kind of makes Batman look like an idiot, to be honest, as he really has no right to tell someone not to brandish a gun after destroying Gotham freeway.

In the real world, Batman could not exist. That should seem obvious. I know that we, as humans, want to idolize our myths, and cling to the hope that something mythological could exist outside the realms of scientific reality, but it’s just not possible. Maybe in a Stephen Hawking future where humans are made superhuman by genetic engineering can we see such a feat, but for now, we are flesh and blood, imperfect and flawed, subject to the laws and rules of physics, and Batman and his fantastic, gravity-defying antics are not even remotely possible, at least not on the scale and duration in which he presents them in comic and movie form. He’s a myth, a god, an icon that has endured a lasting legacy of publication and prominence that’s infused us into debating the possibility of his existence, due to an overwhelming sense of infatuation. I say this as someone with hundreds of Batman comics, toys, posters, etc. I say this as someone who is writing a dissertation on whether or not Batman should kill.

The Question of Morality

This leads us to the moral question of Batman killing his enemies. Born of revenge, Bruce Wayne became Batman to avenge the death of his parents, gunned down in front of him by a two-bit criminal named Joe Chill in a Gotham alleyway. He uses his money to train to fight, acquire lavish and intricate gadgetry, and build a bat costume that is functional for all manner of crime fighting. He’s a vigilante with the means to punch the hell out of bad guys, tie them up, and leave a nice little note for the cops, so they can somehow prosecute without witnesses, warrants, or due process, let alone testimony from Batman himself in court for each case.

So, does that mean that Batman should be like The Punisher and just fly from rooftop to rooftop with guns and grenades and dispatch bad guys into bloody heaps? No, that doesn’t fit his aesthetic. But, could he show up in a warehouse of bad guys and put them all down with chemicals, edged weapons, or some other solution that doesn’t involve guns? Sure. Should he? Well, maybe.

The biggest moral question that befalls a character like Batman is whether the justice he serves saves lives. Beating up a few thugs who are trying to rob someone in an alleyway is one thing. Allowing a mass murderer like The Joker to escape prison time and time again to kill hundreds of thousands of innocent people is insanity. When terrorists attack, be it a lone perpetrator or a group, the response, in reality, is exponential. They are killed or captured, sentenced to life or death in prison, and anyone associated with their crimes is met with similar measure. You can agree or disagree with that, but that is reality and reality is stranger (and far more brutal) than fiction.

I’ve had people tell me that they “don’t believe in war” as if it were a religious doctrine. War exists whether you believe in it or not. I’ve been there. I’ve got the t-shirt. I’ve heard people say they don’t believe in guns. The same thing applies. Some things are irrefutable, like death. Death is a very real possibility of committing violent crime. Yes, prison is also a possibility, but that’s only if you’re brought in alive (and don’t get the death penalty). Rarely is Batman dealing with white-collar crime where he’s taking on nonviolent criminals. Where’s the fun in that? We ultimately want to see Batman be violent. We want to see him hurt bad guys. It’s part of the mythological lesson of the character: punishment (and vengeance) for being a criminal in our society. Break the rules, we break your teeth.

Ultimately, Batman represents our desire to see criminals punished. We want to see them punched, kicked, bloodied, and tossed in jail. It’s a base-level state of ignorant fantasy that creates the simple “lock ‘em up!” reaction when seeing or hearing about a crime on the Internet or news. “Sic the Batman on ‘em!” we may as well say, as the reality of these crimes and the prosecution of them is far more intricate, confusing, and drawn out, sometimes leading to an outright failure of the system and lack of true justice. But, not for Batman. Oh, no. He can punch them and make them feel pain. So, we hold onto that. It’s our quick-hit endorphin rush of instant justice.

But, it’s not reality.

In reality, Batman would be blamed for more deaths than he could ever account for, given his long comic-book (and cinematic) history. Batman’s no-kill rule would be responsible for more innocent deaths than any of his life-saving endeavors. Think of the mass carnage inflicted by his many rogues, all of whom have killed hundreds of thousands collectively. That number would be reduced exponentially if Batman had just killed those guys, just as the military or law enforcement would have done themselves. Beyond that, guys like The Joker would not be breaking out of prison every other week. In comic-book land, the most heavily-guarded prison can easily be broken out of, so long as it suits the story. Not so in real life. Read up on ADX Florence the supermax prison in the United States, if you ever need assurance. Ever heard of an escape from there? There’s never been one. Arkham Asylum, take note.

From a moral standpoint, it’s not only unrealistic that Batman wouldn’t kill, but it’s irresponsible. To not kill The Joker or Riddler or any of the violent offenders that continue to haunt the world and claim countless innocent lives, is a disregard for innocent lives altogether. Beyond that, if Batman wasn’t killing these guys, the government, law enforcement, or even a citizen, would get the job done for him. How Batman could continue to suit up and keep doing the same thing over and over again with no new result is pure insanity and would be an indicator that he’s just another weirdo in a costume, rather than a solution to the world’s (let alone Gotham City’s) problems.

Ask yourself if one of your family members was a victim of any of Batman’s countless rogues, would you consider him still to be a hero, knowing that he could’ve ended their reign of crime and numerous breakouts long ago?

Should Batman Kill?

If you came into this looking for a definitive yes or no, then I’ve already lost you. If anything, the complexity of portraying a modern myth, one that is handed off from creator to creator to creator over decades of storytelling creates a conundrum of character. There is no definitive yes or no on whether or not Batman should kill. But, by that token, that means that there’s nothing to say he absolutely should have a no-kill rule. Nor that he shouldn’t.

But, if you want to really break it down, the answer is irrelevent. Batman HAS killed, and he’s done so in every medium that he’s appeared, from comics to film to animation to video games. So the question of whether he should or shouldn’t becomes more like: Should he continue to kill or continue to refrain from it?

My take on who and what Batman should do, given all of the aforementioned information I’ve presented here, from the definition of myth, the history of the character in print, the censorship that became canon, the bounds of reality vs. fiction vs. morality, and the place he now finds himself in the modern-day cultural landscape is thus:

I don’t think that Batman should kill with guns or on a level of violence that someone like The Punisher does, even if their origins are similar. Batman is without superpowers, but he is a different man, born under different circumstances, and pursuing a different mission than Frank Castle aka The Punisher.

However, I don’t think a no-kill rule is feasible in any regard for Batman, nor should it be. It robs his character of having to make any really tough decisions, because we always know his endgame is that he’ll never kill, so it will always be some kind of moral grandstanding message coupled with a few bloody punches for good measure and off to Arkham the bad guys go. If that’s enough for those wanting some escapism, fine, but those same people need to keep out of the no-kill argument. It really doesn’t concern them, because they aren’t invested beyond the base-level popcorn thrill of the character.

I would propose (and this is how I would write Batman if ever given the opportunity) that Batman takes on this mantra:

I don’t want to kill, but I will if I have to. And sometimes, I have to.

What this creates is the chance for Batman to retain his humanity, but also allows him to act decisively if the situation calls for it. He can operate from a place of punching, kicking, gassing, tying up, or otherwise incapacitating his enemies, but if it’s a case of them vs. me, them vs. innocents, or them repeatedly committing acts of violent crime, then he has the authority, obligation, and commitment to put an end to it for good.

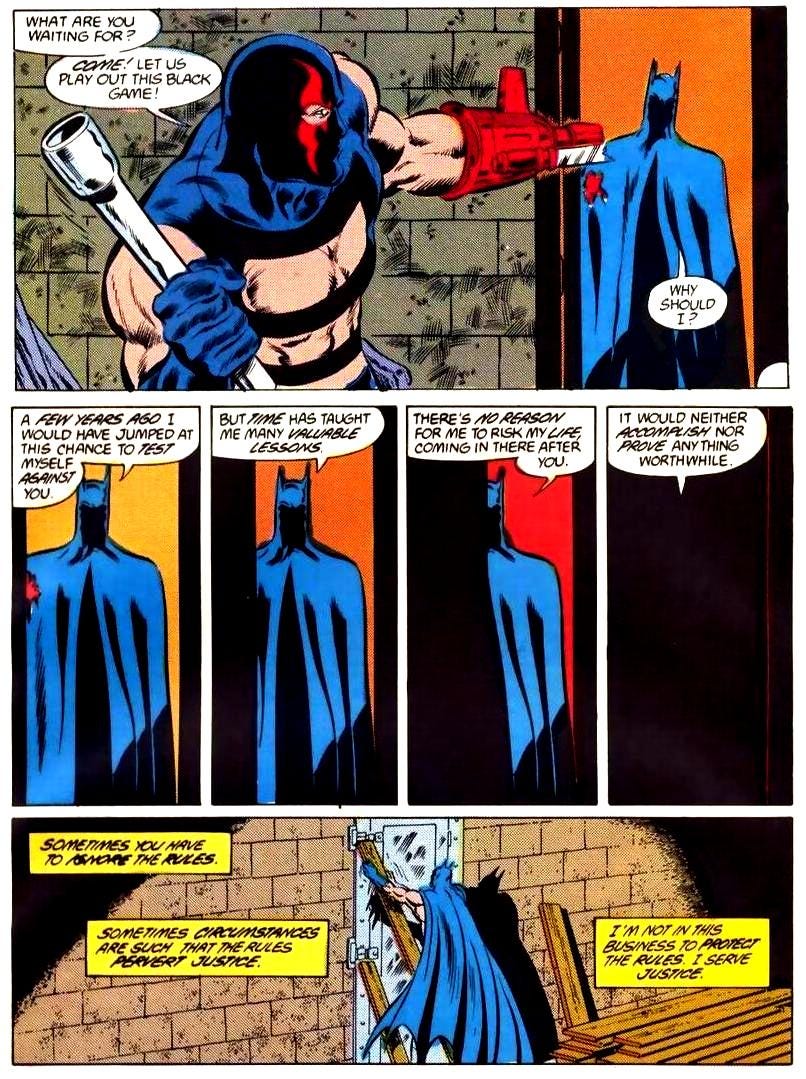

By that same token, it allows him to enter a situation with his parameters set. If he must go in bringing death and there’s no other option, then so be it. He can still attempt every possibility to not kill, but if it simply isn’t possible, then he will do what he must, IE Escalation of Force. Batman’s quest for justice within the bounds of his mission has been at the centerpoint of his persona, and my point has already been demonstrated, most notably in The KGBeast storyline by writer Jim Starlin and artist Jim Aparo (See Below):

I have dealt with the decisions of having to kill or not kill as a soldier. When at war, at least in modern warfare, you are given a set of Rules of Engagement (ROE), which dictates what actions you can take in engaging and killing an enemy. A running joke would be how frequently that changes (sometimes weekly). It creates utter chaos in war. One day you can shoot at anything, the next day you can only shoot at certain things from certain distances in certain uniforms, etc. It’s mass confusion and has led to more than a few criminal cases against soldiers. It’s ironic that men in suits that have never stepped on a battlefield are out there making up ROE for those that pull the triggers (and folks wonder why we aren’t “winning” wars).

Batman doesn’t have to deal with that, because he can set his own parameters. Having a clear code to follow would allow Batman to dispense justice in a way that’s measurable. In the end, he is not an officer of the law, nor a soldier, nor any kind of lawful agent of the government or the people. He’s a vigilante. Giving him a “will-kill if necessary” code instead of a “no-kill” makes more sense for his character. It also makes him more interesting, more complex, and provides the means to explore him in a manner that’s unchained to a degree, but still guided by a moral compass.

Since comic-book characters, our new modern myths, have morphed and changed throughout the years, it’s perfectly reasonable for Batman to evolve his code, especially one that was born of censorship and sales anyway. We live in a time where injustices, crimes, war, and terror are thrust upon us instantaneously with social media and 24-hour news cycles. It certainly creates the illusion that it’s more violent than ever (it’s not). A reflection of this and the fact that we can now see the realities and consequences of violence directly, in the palm of our hands, means that the myths we worship need to get with the times as well.

Yes, they may exist in many ways to reflect our desire for a better nature, but if our better nature is inaction, then what are our heroes actually doing for us besides providing mindless, unchallenging entertainment? And if that’s all it is, then why does the debate exist at all? It’s okay to want more from our myths, our heroes, even our entertainment. Perhaps this debate will always exist, and maybe that’s the way it should be. Keeping the debate alive, after all, proves that we still care enough to explore who our heroes should be, how they reflect us, and ultimately, who we want to be vs. who we really are.